Combination products are used routinely and highly effectively in ophthalmology. Specialist practitioners value their particular utility when it comes to delivering therapies or additional therapeutic benefit by means of a complementary element. But by their very nature – distinct constituent parts packaged together as a single offering – combination products pose significant regulatory obstacles. I’m going to walk you through those challenges and help plot a path to market.

As we know, in healthcare regulatory approval is gold dust. Every project should have a strategy for regulatory compliance embedded at the earliest opportunity. And when it comes to combination products, this process must be handled carefully.

Not only is their regulation complex, but significant differences exist between the European and US markets. Nevertheless, certain truisms prevail across borders. Say you are a drug, biologics or cell therapy manufacturer and are thinking of combining your product with a device. Your pharma quality management system (QMS) and current good manufacturing processes (cGMP) will need to be updated to incorporate the regulatory expectations for the device. Conversely, a manufacturer switching up their device for use alongside an active element – drug, biologic or cell therapy – will need an upgraded QMS to comply with the regulations that apply to the active element.

Want to learn more?

Defining combination products

Let’s get down to basics and begin with the definition. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) says a combination product is one that comprises an active element (drug, biologic or cell therapy as above) and a delivery system, such as a syringe. The combination product term is informally used in the context of other regulatory areas, though not necessarily defined. This is the case with the Medical Device Regulation (MDR) in the EU.

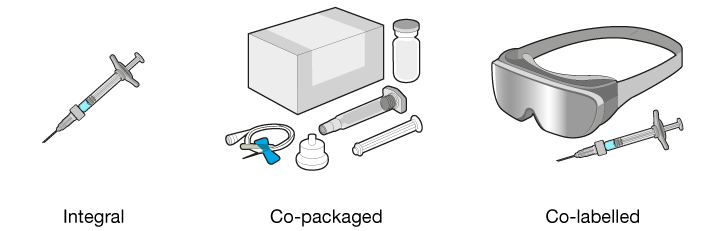

As for variations, combination products may be one of the following:

- Integral – the constituent parts are combined into a single product, for example a prefilled syringe

- Co-packaged – the constituent parts are not combined into a single product but are provided in the same packaging, for example a drug in a vial, a vial adapter, and a syringe

- Co-labelled – the constituent parts are not provided together but the labelling indicates that they must be used together, for example, a cell-therapy filled syringe for intraocular injection and goggles

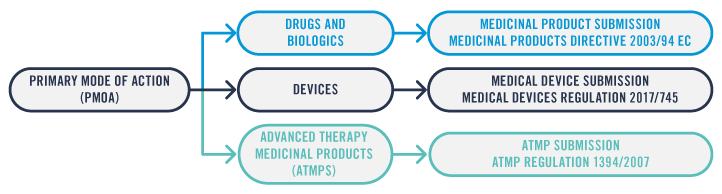

First, I’m going to reveal the European regulatory process for integral and co-packaged combination products. The first step towards identifying the correct submission type and the associated regulations is to determine the Primary Mode of Action (PMoA) of the combination.

An integral combination product with the active element as the PMoA will be submitted to the regulators as either a Medicinal Product for drugs and biologics or an Advanced Therapy Medicinal Product (ATMP) for cell therapies. The device element of the combination product will need to comply with the applicable General Safety and Performance Requirements from the Medical Device Regulation (MDR).

An integral combination product with the device as the PMoA combined with a drug or biologic will be submitted to the regulators as a Medical Device. The active element of the combination product will need to comply with the applicable requirements from the Medicinal Products Directive or the ATMP regulation, as appropriate.

For a co-packaged combination product, the Medical Device part must be submitted to regulators as a Medical Device and will need to meet CE marking requirements according to the MDR whilst the active element will need to comply with the applicable requirements from the Medicinal Products Directive or the ATMP regulation, as appropriate.

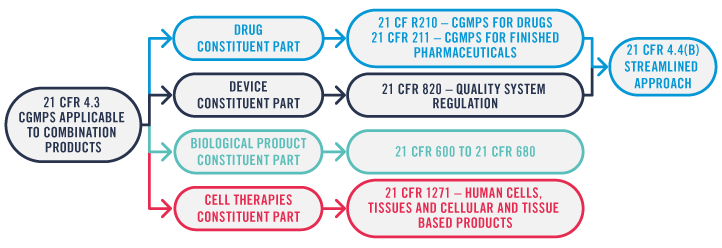

Over to the US now, where the applicable regulations may vary depending on the constituent parts of the combination product and how the combination product is marketed. Here, it’s a case of active element plus device combination products (integral or co-packaged). If the combination product’s active element is a drug rather than a biologic or a cell therapy, and regardless of the PMoA, the combination product’s submission may follow the streamlined approach defined by 21 CFR 4.4(b), limiting the amount of information required for the different constituent parts of the combination product.

This enables the Marketing Authorisation Holder (MAH) to choose the optimal path based on their existing Quality Management System (QMS) – be it drug or device based – ensuring that the required elements from the regulations are covered.

However, if the combination product includes a biologic or a human cell, tissue and cellular and tissue-based product (HCT/P) as a constituent part, in addition to the requirements for the drug and device constituent part, all applicable cGMP requirements for the biologic or HCT/P need to be complied with. This puts a greater burden on the MAH’s QMS.

Co-labelled medical devices

Now let’s turn to co-labelled products. From a regulatory perspective, the two components of the final product need to be considered independently, as neither is effective by itself without the action of the other. Take as an example the goggles used to enhance the properties of a gene therapy delivered to the eye by intraocular injection. Such goggles are typically used to augment the amount of light received by the patient, as the gene therapy alone is not enough in an ambient light environment, or even bright sunlight.

The goggles could potentially be marketed in their own right. In the EU, the gene therapy would follow the Advanced Therapies Medicinal Products (ATMPs) regulation. In the US, if the PMoA cannot be determined, the FDA’s Office for Combination Products will assign the review to the most appropriate centre.

The goggles could potentially be marketed in their own right. In the EU, the gene therapy would follow the Advanced Therapies Medicinal Products (ATMPs) regulation. In the US, if the PMoA cannot be determined, the FDA’s Office for Combination Products will assign the review to the most appropriate centre.

The goggles may be marketed as a Medical Device, complying with the requirements laid out by the MDR in the EU and by 21 CFR 820 in the US. If not marketed as a Medical Device, the MAH of the combination would need to ensure that their manufacture and performance when used alongside the cell therapy is safe and effective for the intended use of the combination.

Another good example is photodynamic therapy, where light of a specific wavelength is used to activate light sensitive therapy. Neither is beneficial to the patient without the other. The main difference between this and the previous example is that the diffuser used to direct the light source is unlikely to be marketed in its own right, as it is developed specifically to be used to enable activation of a particular therapy.

Product usability is vital

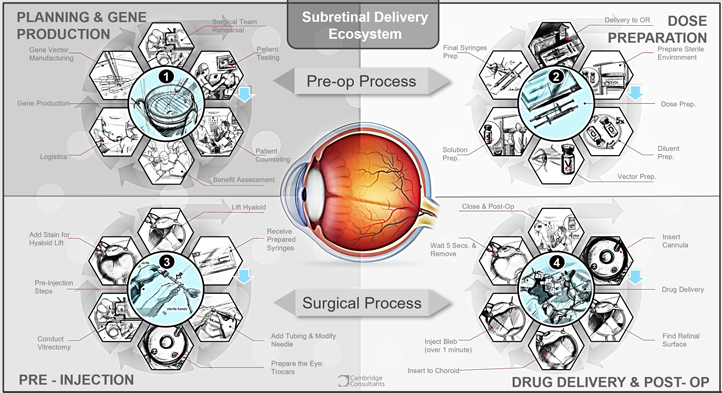

The usability aspect of the product also plays a big part in the development and submission, as well as on the uptake of the therapy by the target users. Let’s take, for example, the ecosystem of a sub-retinal delivery system, specifically, dose preparation.

It is not uncommon to carry out early stage clinical studies for drugs and biologics with different preparation and delivery methods to those intended for the commercial product – extracting a given volume of drug from a vial rather than using a prefilled syringe, for instance. But it is important to acknowledge that overly complex methods may be cumbersome and lead to errors or wasted product during preparation or delivery of the drug.

The labelling for the marketed product will require instructions on these methods which need to have been validated during the development process. Information on the usability of the product can be obtained from human factors engineering usability trials. In addition to these, clinical trials for the drug product can also be used to identify and explore improvements to preparation and delivery steps.

When compared to other injection products, the preparation of some therapies prior to administration involves a long list of items (syringes, vials, needles), a class II vertical laminar flow Biological Safety Cabinet (BSC), a dilution step, and a complex preparation sequence involving two operators before final assembly of the prepared syringe with the subretinal injection cannula in readiness for surgery.

There are a number of potential issues with this which need to be considered:

- The requirement to have two BSC trained staff available to prepare the product

- The requirement to have a suitable clean area incorporating BSC cabinets near the operating room

- Concerns with sterility

- Time-limitations – the need to be prepared within 4 hours of administration

- Handling/transportation from preparation area to operating room

Additional considerations

In summary then, the task of identifying the correct submission route and associated regulations is only part of the process. There are a number of additional considerations that the manufacturer or MAH needs to take into account when developing a device or combination product. They include whether the product is based on a marketed predicate; the classification of the device element; whether the device is to be implanted and the usability of the product – not forgetting any required preparation steps as well as the delivery method.

The positive impact and added simplicity offered by a delivery device that does not require cumbersome preparation steps cannot be overestimated. A readily available device provides a number of advantages. For example, no preparation is required other than removal of the delivery device from its packaging immediately prior to use. Also, sterility of the delivery device and the drug/biologic is assured at the time of manufacture of the drug/biologic and delivery device, as well as at the time of filling.

What can the manufacturer or licence holder do about this? It might be a good idea to explore alternative methods of combining the drug/biologic with a delivery device. This means considering not just the practicalities of something like a prefilled syringe but also ergonomics and ease of handling. Here, it is helpful to talk to surgeons and ask about their preferred delivery method. If a prefilled delivery device is not an option, nurses and clinicians who will be doing the preparation should be consulted before the procedure is finalised and included in submission documentation.

Please do email me if you’d like to discuss any aspect of this topic in more detail. It would be great to continue the conversation one-to-one.